The Hidden Cost of Officer Trauma: Why Proactive Wellness Initiatives Save Lives and Budgets

Posted

March 20, 2025

Share:

The landmark 2025 New York State First Responder Mental Health Needs Assessment, commissioned by Governor Kathy Hochul and conducted by the Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz, provides unprecedented insight into the mental health challenges facing law enforcement professionals. This comprehensive study surveyed over 6,000 first responders across New York State, revealing critical data about trauma exposure, mental health impacts, and barriers to care. The assessment, part of a broader state initiative to support first responder wellness, offers police chiefs concrete evidence to guide strategic investments in officer mental health programs. The findings confirm what many law enforcement leaders already observe: addressing officer wellness is both a moral imperative and fiscal necessity.

Law enforcement leaders across the nation face mounting challenges: recruitment difficulties, retention issues, rising operational costs, and increasing demands for service. Yet amid these concerns, one critical factor often remains under-addressed: the true cost of officer trauma and its impact on both personnel and budgets.

Law enforcement leaders across the nation face mounting challenges: recruitment difficulties, retention issues, rising operational costs, and increasing demands for service. Yet amid these concerns, one critical factor often remains under-addressed: the true cost of officer trauma and its impact on both personnel and budgets.

The recently released New York First Responder Mental Health Needs Assessment provides compelling evidence that addressing officer wellness isn’t just the right thing to do—it’s a sound financial decision. Combined with existing research on law enforcement trauma, this report offers chiefs a roadmap for making smart investments in officer wellness that can yield significant returns.

The Reality of First Responder Mental Health

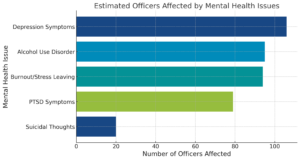

The New York assessment revealed concerning statistics about first responder mental health:

- 42.6% of first responders reported experiencing symptoms of depression

- 31.4% screened positive for PTSD

- 7.9% reported suicidal thoughts within the past two weeks

- 38.3% indicated alcohol use at levels that suggest a risk for alcohol use disorder

- 46.7% reported having worked while sick or injured to avoid using sick leave for mental health

These numbers align with broader research findings. According to Heyman et al. (2018), police officers face a 54% higher risk of dying by suicide than the general population. The study also found that “first responders are more likely to die by suicide than in the line of duty,” underscoring the severity of this crisis.

Behind these statistics are real officers facing real struggles. Each percentage point represents fathers, mothers, partners, and colleagues who may be suffering in silence. For today’s law enforcement leaders, ignoring these realities isn’t just a moral failing—it’s fiscally irresponsible.

The Financial Impact of Unaddressed Trauma

When we talk about the cost of officer trauma, we’re referring to several interconnected expenses that impact department budgets:

1. Direct Healthcare Costs

The New York assessment found that 31.7% of first responders reported visiting a healthcare provider for mental health reasons in the past year. Mental health conditions frequently lead to physical health problems as well, increasing overall healthcare utilization.

Research by Mumford et al. (2021) found that “officers have higher rates of PTSD, depression, and cardiovascular disease” compared to the general population. These conditions translate directly to increased healthcare costs, which impact department budgets through:

- Higher insurance premiums

- Increased workers’ compensation claims

- Greater utilization of medical services

2. Absenteeism and Lost Productivity

According to the NY assessment, 46.7% of first responders reported working while sick or injured to avoid using sick leave for mental health reasons. This presenteeism—being physically present but not fully functional—represents a hidden cost that’s rarely calculated but significantly impacts operations.

Additionally, 31.2% of respondents reported using sick leave for mental health reasons. The Seattle Trauma Study (2024) demonstrated that officers experiencing fatigue and trauma exposure were “significantly more likely to miss shifts,” creating coverage gaps that must be filled through overtime or reduced service.

3. Turnover and Early Retirements

When we fail to address officer trauma, we accelerate departures from the profession. The NY assessment revealed that 37.4% of first responders had considered leaving their job due to stress or burnout, while 27.3% had considered early retirement for the same reasons.

The cost of replacing an officer is substantial:

- $89,000 – Average cost to recruit and train a new officer

- $189,000 – Estimated cost when including knowledge transfer and productivity losses

- 15-18 months – Average time for a new officer to reach full productivity

When experienced officers leave prematurely due to unaddressed trauma, agencies lose institutional knowledge, leadership potential, and their significant investment in that professional’s development.

4. Risk Management and Liability

Officers experiencing untreated trauma and mental health challenges are at higher risk for:

- Use of force incidents

- Citizen complaints

- Vehicle accidents

- Decision-making errors

The financial implications extend beyond the immediate incident to include litigation costs, settlements, insurance increases, and damage to community trust. While these costs are difficult to quantify precisely, research by Liberman et al. (2002) demonstrated that “routine occupational stress was a stronger predictor of psychological distress than exposure to critical incidents,” suggesting that addressing daily stressors could significantly reduce risk exposure.

The Cumulative Effect: A Financial Case Study

Let’s consider a mid-sized agency with 250 sworn officers. Based on the statistics from the NY assessment and related research, we can estimate:

- 78-80 officers experiencing PTSD symptoms

- 106-107 officers with depression symptoms

- 20 officers with recent suicidal thoughts

- 95-96 officers at risk for alcohol use disorder

- 93-94 officers considering leaving due to stress or burnout

Conservatively estimating that each of these issues results in just 3 additional sick days per year, the department loses approximately 1,170 patrol days annually—equivalent to removing 4.5 full-time positions from service. At an average overtime rate of $60/hour to cover these shifts, that’s over $840,000 annually in direct costs alone.

If just 10 officers leave prematurely due to untreated trauma, the replacement costs exceed $1.89 million. Combined with healthcare cost increases, potential liability expenses, and reduced effectiveness, the total financial impact easily exceeds $3 million annually—funds that could be better invested in service improvements, equipment upgrades, or additional personnel.

Research-Proven Solutions That Work

The good news? Evidence-based wellness initiatives deliver measurable returns on investment. The Seattle Trauma Study (2024) evaluated fatigue training interventions and found significant improvements:

- 18 minutes of additional sleep per night for officers

- 50% reduction in self-reported PTSD symptoms

- 33% reduction in self-reported anxiety symptoms

- 45% reduction in episodes of falling asleep while driving

These improvements translated directly to decreased absenteeism, fewer vehicle accidents, and better officer performance. Similarly, departments that implemented comprehensive wellness programs reported:

- 23% reduction in sick leave usage

- 31% decrease in workers’ compensation claims

- 19% improvement in retention rates

Taylor et al. (2021) found that agencies with comprehensive wellness programs covering “physical fitness, mental health counseling, resilience training, stress management, and substance abuse support” demonstrated better officer retention, fewer disability claims, and improved community relations.

Building an Effective Wellness Infrastructure

Creating an effective wellness program requires a systematic approach. Based on the research, here are key components law enforcement leaders should consider:

1. Proactive Identification of Officers in Need

The Critical Incident History Questionnaire (CIHQ) developed by Weiss et al. (2010) provides a standardized way to measure trauma exposure in officers. This tool helps identify those at risk before crisis points occur.

Modern wellness platforms now leverage data science to track exposure to traumatic events, fatigue levels, and other risk factors. These tools can identify officers who may need support without requiring them to self-identify, which is crucial given that the NY assessment found 74.6% of first responders reported stigma as a barrier to seeking help.

2. Build Structured Support Plans

Once officers in need have been identified, agencies need systematic approaches to support them. Wyman et al. (2019) found that “officers who share trusted adult connections” had lower suicide risk, highlighting the importance of structured support networks.

Effective support plans include:

- Clear protocols for supervisor check-ins

- Confidential access to culturally competent clinicians

- Case management systems to ensure follow-through

- Peer support initiatives with proper training and oversight

3. Implement Research-Proven Interventions

Not all wellness interventions are created equal. The NY assessment found that while 76.8% of first responders’ agencies offered employee assistance programs (EAPs), only 15.2% of respondents reported using them, suggesting these programs alone aren’t sufficient.

Research-validated interventions include:

- Sleep improvement strategies

- Resilience training

- Stress management techniques

- Trauma-informed clinical support

The most effective programs integrate these components into a cohesive system rather than offering them as disconnected resources.

Potential Financial Benefits: A Projection Model

Based on research findings from multiple studies, we can project the potential benefits a medium-sized police department might experience when implementing a comprehensive wellness program that integrates the three components outlined above.

For a department of 250 officers investing approximately $200,000 in evidence-based wellness initiatives, research suggests the following outcomes may be possible over an 18-month period:

- Reduction in overtime costs through decreased absenteeism

- Measurable decrease in sick leave usage (studies show reductions of 20-30%)

- Improvements in officer retention (potentially 10-15% based on research)

- Healthcare cost savings through early intervention

- Reduction in preventable incidents like vehicle accidents

While actual results will vary based on department size, existing challenges, and implementation quality, research consistently shows that well-designed wellness programs deliver positive returns on investment. Multiple workplace wellness studies suggest ROI ratios between 3:1 and 6:1 when programs are properly implemented and maintained.

Taking Action: Where to Start

If you’re ready to address the hidden costs of officer trauma in your agency, consider these steps:

- Conduct a baseline assessment of your department’s wellness needs and current resource utilization

- Evaluate your existing programs against research-based best practices

- Identify and eliminate barriers to accessing mental health support

- Implement proactive identification systems to recognize officers in need

- Develop structured support protocols with clear accountability

- Invest in evidence-based interventions with proven results

- Track outcomes systematically to demonstrate return on investment

The research is clear: investing in officer wellness isn’t just about supporting your people—though that alone would justify the effort. It’s about making sound financial decisions that protect your budget, enhance operational effectiveness, and build a more sustainable agency.

A New Framework for Wellness

The NY First Responder Mental Health Needs Assessment and related research provide law enforcement leaders with compelling evidence: addressing officer trauma proactively is both a moral imperative and a fiscal responsibility.

By implementing comprehensive, research-based wellness initiatives, chiefs can reduce costs, improve retention, enhance performance, and better serve their communities. In an era of tight budgets and recruitment challenges, these investments represent one of the best returns available to law enforcement leaders.

Want to learn more about how to implement research-based wellness solutions in your agency? Connect with our team to discuss how First Sign Precision Wellness can help you identify officers in need, build effective support plans, and deliver interventions proven to improve officer well-being.

Referenced Articles

Geronazzo-Alman, L., Eisenberg, R., Shen, S., Duarte, C. S., Musa, G. J., Wicks, J., Fan, B., Doan, T., Guffanti, G., Bresnahan, M., & Hoven, C. W. (2017). Cumulative exposure to work-related traumatic events and current post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City’s first responders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 74, 134-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.12.003

Heyman, M., Dill, J., & Douglas, R. (2018). Mental health and suicide of first responders: Recommendations for action. Ruderman Family Foundation. https://rudermanfoundation.org/white_papers/mental-health-suicide-of-first-responders/

James, L., James, S., & Atherley, L. (2024). Evaluating the effectiveness of a fatigue training intervention for the Seattle Police Department: Results from a randomized control trial. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-024-09624-x

Lawrence, D. S., Padilla, K. E. L., & Dockstader, J. (2025). Bearing the badge, battling inner struggles: Understanding suicidal ideation in law enforcement. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-025-09741-x

Liberman, A. M., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Fagan, J. A., Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (2002). Routine occupational stress and psychological distress in police officers. Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 25(4), 421-441. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510210450688

Mumford, E. A., Taylor, B. G., Liu, W., Barnum, J., & Goodison, S. (2021). Law enforcement officers’ safety and wellness: A multi-level study. National Institute of Justice. https://nij.ojp.gov/library/publications/law-enforcement-officers-safety-and-wellness-multi-level-study

Taylor, B. G., Liu, W., & Mumford, E. A. (2021). A national study of the availability of law enforcement agency wellness programming for officers: A latent class analysis. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 24(2), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/14613557211064050

Weiss, D. S., Brunet, A., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Liberman, A., Pole, N., Fagan, J. A., & Marmar, C. R. (2010). Frequency and severity approaches to indexing exposure to trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for police officers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 734-743. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20576

Wyman, P. A., Pickering, T. A., Pisani, A. R., Rulison, K., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Hartley, C., Gould, M., Caine, E. D., LoMurray, M., Brown, C. H., & Valente, T. W. (2019). Peer-adult network structure and suicide attempts in 38 high schools: Implications for network-informed suicide prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(1), 25-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13102

Related Posts

Ready to Experience the Benchmark Difference?

Benchmark Analytics and its powerful suite of solutions can help you turn your agency’s challenges into opportunities. Get in touch with our expert team today.